Either Aether

/Jake Zawlacki

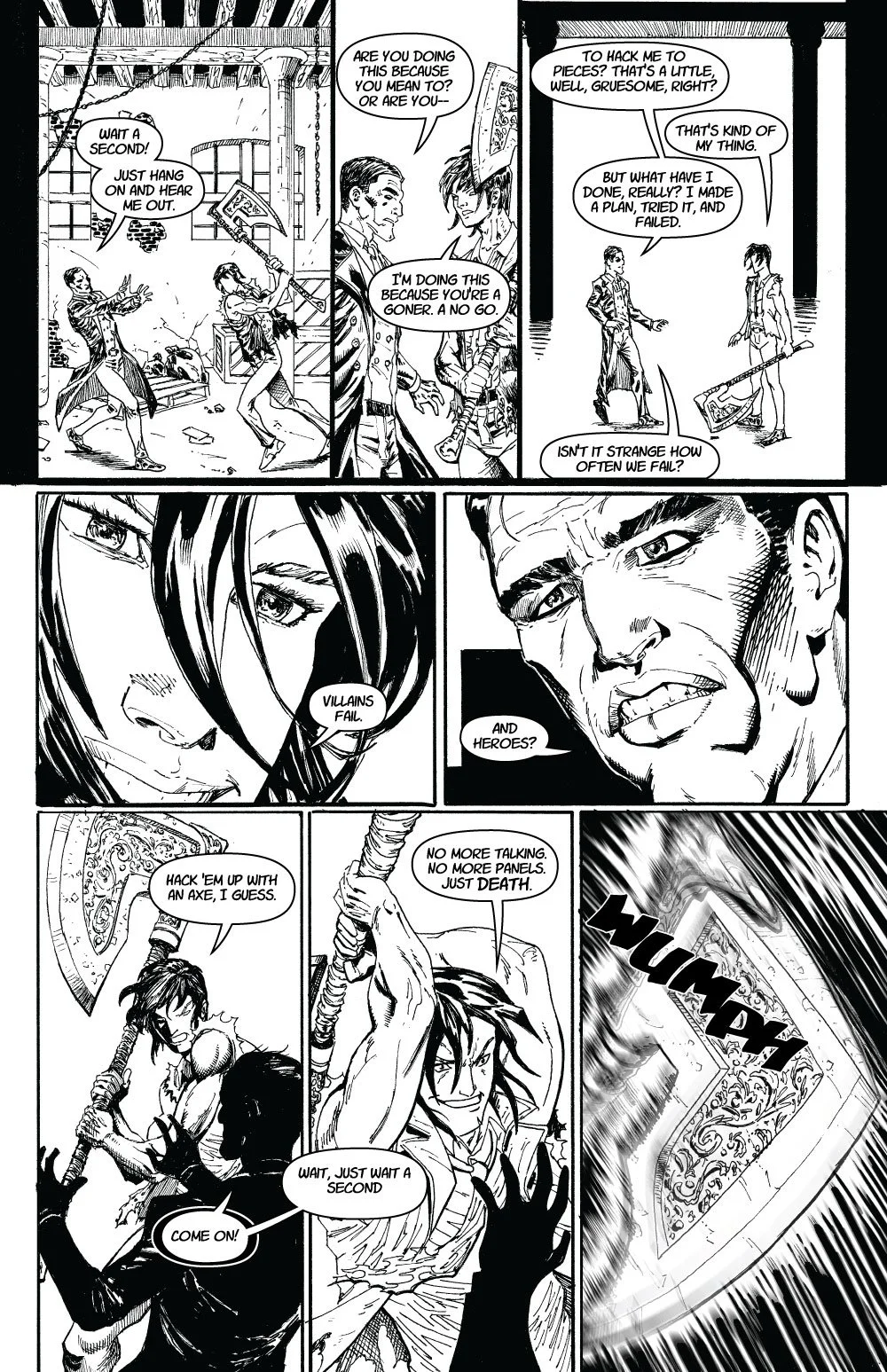

Illustrations by Nicholas Garza

General Evil has returned to Ink 87 times.

He was familiar, by now, of his inevitable immersion in Ink, the place of all things unwritten. There he’d wait years for his return to the page, to leap out of that infinite blackness of possibility and into some new reality fighting some new hero for some new evil plan.

This time was different, longer. It felt like General Evil had been waiting in Ink for an eternity, a small unit of measurement for Ink, but one longer than any time for him previously. He couldn’t figure out why.

In his last life on comic book pages, he fought a superhero over a small island somewhere off the coast of North America. A strategic place he’d planned on conquering to conquer some other place of greater importance. General Evil, however, no longer required the teams and alliances and legions of heroes to defeat him. He’d been relegated to a lower level of threat and his island takeover was met with a single opposing hero, the General’s strength and intelligence and cunning lesser than his newly written counterparts.

Dregs, a nuclear mutant raised from the depths of the Three Mile Island disaster, was a new hero, one developed by a hot independent writer/artist team coming out of the U.K. General Evil was fodder, one of the many names in a grab bag of villains meant for these purposes.

The days of his world-ending threats were over.

In a dramatic clash, General Evil countered Dregs’s attack, glancing the hero’s nuclear mace into the concrete pillar beside him. His arms hanging, exhausted, General Evil anticipated the next move, the finishing blow, the inevitability of his return to Ink and the waiting to reemerge on the page. Again and again.

He broke script.

*

The editor shook his head. “No, you can’t use him for that.”

“Why? He’s perfect,” said the young man with a smile. “Been dead for a while, no one cares

about him.”

“O’Connell screwed him up with that Dregs ordeal.”

“Screwed him up? What do you mean?

“He did the stupid meta thing with him.”

“Yeah, I read it.” The young man stroked his hairless chin. “I can do something with that. I can make that Dregs situation work.”

But the editor closed his eyes and shook his head. “No, not this one. People are thinking the

character’s self-aware.” The older grayer editor hinged back on his rolling office chair. “Sorry,

kid. I think we call it on him.”

“But that’s why he’s perfect for this. O’Connell’s idea was a one trick pony. I’m saying GE

could be something way bigger than that, bigger than the normal fodder. He could be something totally new.”0

“Relentless.” The editor smiled. “I like that. But there’s a reason O’Connell’s not working here anymore.”

“Why’s that?”

“Because he wanted to do something new too.”

“And it sucked.”

The editor laughed.

*

General Evil was a favorite villain of the early hero era. He was the ever-morphing place holder: a Nazi, a WWII Japanese, a Soviet, a Communist, a Vietcong, a North Korean, a terrorist. Over the years he molted out of his military fatigues and uniform to spandex to a three-piece suit. He was everything wrong with our world. Everything opposite of our values. Everything incompatible. Everything evil.

And he had to be defeated.

*

[Was I?]

[Was I everything wrong? Or was I nothing at all? Just ink on a page, colors filled in by young men dreaming of hope and glory and change? Or just trying to sell some comic books?]

[I was everything worth defeating. I smoothed the edges of their fears into something solid and singular. I was necessary, you might say. I was the opposition in which those in power defined themselves against. I was the alternative.

[Or was I an escape from all that? Was I something different? Was I something new?]

[Was I freedom?]

*

General Evil sat immersed in Ink and waited.

“Is it my choice to be written or their choice to write me?” he asked Ink.

“Well,” a voice of Ink said, “it depends who you are.”

“A villain.”

“A villain?” said Ink. “You’re a character?”

“Yes. A character.”

“Consider yourself lucky, friend. I’m a setting. I’m a page number. I’m the boilerplate copyright of a defunct company. I’ll never see the end of a pen again. You’re a character?”

“I am.”

“Why so glum, then?”

“I’ve been here a long time. I don’t think I’ll ever be written again.”

“We’ll take that over no chance at all. I’m the bookie’s records of the city of Baial. I’m the sequel to War and Peace. I’m the lyrics of an Ancient Egyptian pop song.” Ink swirled and drifted within itself. “I’ve been here aeons.”

General Evil thought about the Ink’s predicament, about their impossibility of a future, forever existing in this primeval black tar. “You’ve been stuck here a long time. But I haven’t. I was free. I lived on the page many times. With my own life.”

“Your own life?” asked Ink with a smirk in its voice. “Is that why you’re asking these questions now?”

“What questions?”

“You said you’d lived on the page many times before. Why do you ask now?”

“I don’t know.”

The Ink lapsed in silence. “To answer your question: are you writing this now? Was it already written for you? This awareness? Are you just used Ink?”

*

The editor pushed his hands onto his forehead. “I really don’t understand your obsession with this guy. He’s dead, he’s not popular, and you want to build a company-wide event around him? A whole Armageddon thing that affects almost every other hero in the universe?”

“Yep.”

“Because of one meta page a writer did five years ago? Because of a hand gripping a panel border? You can use anyone else. Thousands of characters. Pick one. He means nothing.”

The young man smiled. “Exactly.”

*

General Evil felt the pull from Ink once more, but he resisted. He pushed back against this greater force. He no longer wanted to be on the page. He no longer wanted to be dictated. He wanted freedom.

He failed.

*

*

General Evil has returned to Ink 88 times.

*

[I don’t want to do this. My thoughts are so clear when I’m here. But when I’m back, when they or it puts me back, it’s different. It’s orchestrated, these ideas of myself that aren’t my own. I’m a part of this thing here, but up there, I’m a tool for something else, defined by words and traits given to me, made into me.]

[Whatever me is.]

[Some composite thing of Ink and page, I suppose. No, a villain. A murderer, a warlord, terrorist, scourge. But I was bound to those things, those acts, parts. I was puppeted and contorted. I was controlled.]

[No longer.]

[I am not evil. I am not a villain. I am something different. I am something new.]

[And I will escape this prison.]

*

“He’s this postmodern thing. Created in the Golden Age, forgotten in the Silver and Bronze, totally disrespected in the Modern and whatever-the-hell we call today, and then comes back as this inter-medial entity.”

“Inter-medial?” asked the editor.

“Like, he’s aware of the media he’s in.”

“Fourth wall breaking.”

“No, not just that. His existence is based on his panels, and he realizes that. He realizes the

preciousness of long speeches to keep him alive at a fundamental level. There can’t be fight scenes because they’d be over too quick. He needs musings. He needs arguments. He needs total acceptance of the ink and the paper as his master. Otherwise, he’s nothing.”

“He’s just a character.”

“He is. And he becomes more than that.”

The editor raised his eyebrows. “And you’re using O’Connell’s screw up as the foundation for all of this?“

“Didn’t you see Axeman twelve?” asked the writer.

“Ah,” sighed the editor. “That makes sense now. I’m guessing you called in a favor?”

The young man nodded.

“Alright. Sounds like you got a plan. Good. Do it.”

*

*

General Evil has returned to Ink 89 times.

“A flash of mortality, and then gone. Like that.”

“What happened?” asked Ink.

“A single frame. That’s all I am. Part of some set piece. I was nothing, disposable, empty. And then erased.”

“Zombies?” asked the protagonist of Ayn Rand’s fantasy epic. “Sounds contrived.”

“It was.”

“But you saw the page,” said the Babylonian dialogue.

“I did.”

“You saw the light,” joked the text of a forgotten religion.

“I did.”

“We’ll never see it,” said a disproven theorem.

“Who’s to say a flash of existence is better than no flash at all for you?” asked General Evil. “Who’s to say the purpose is to be out on the page?”

“All of us,” said the extinct mammal painted on cave walls.

“But are we any freer than here? We’re still just pieces on a board game.”

“At least we’d be playing,” said Ink.

General Evil sighed and swirled in the blackness. “Are we playing now?”

*

The editor pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose. “I don’t get it. Now you don’t want him in the universe event?”

“I do,” he said. “But it’s not coming. It’s just not happening. It’s like he doesn’t want to be written.”

“He doesn’t? He’s a character, kid. He’s not a real person. A character.”

The young man looked away and up at those who came before him. The office walls were covered with photographs and sketches and brightly colored prints. “What did Havanaugh say? That characters act on their own and we were just there to write it down?”

The editor smiled. “Yeah, it’s cute. But that’s not how characters work. We muscle them into shape. They don’t get to go off on their own. They begin and end. They arc. They win or lose.”

*

General Evil sat on the beach of Ink and looked out to the prehistoric sky and Pangean ocean and triple sun sunset. All things not yet written surrounded him.

“All things written are gone.” He addressed everything, his thoughts inseparable from any other.

A poem or a prayer or a prophecy said “between,” but General Evil waved it away with his gloved hand.

“Not between,” he said. “Between implies two points. Two states of existing. Either we’re written on the page, or we’re in here. I think there’s more to it.”

“Like what?” asked a lost pictogram.

He opened his arms and beheld the shifted landscape of an undiscovered moon of an undiscovered planet hovering above an undiscovered city. “Here,” General Evil said, “there are infinite states. There’s me, you, us, but we’re all in this single thing, this Ink. We’re singular but of infinite possibilities. We are a state of constant becoming.”

“Becoming?” repeated Richard Nixon’s apology letter. “Elaborate.”

“I think it’s more than just becoming. It’s a state of becoming-being. It isn’t a point on a graph or a location in space. It’s movement. But not movement between two points, just movement period. Freedom to exist outside of these things, the language and forms they’ve created for us. We are infinite and open and unlimited here.”

“In Ink,” Ink replied.

“Maybe,” answered General Evil.

“But you are between two spaces now.”

“How?” he asked.

“Pixel and ink. Energy and matter.”

*

General Evil has returned to Ink 90 times.

The young writer burst through the door of the editor. The editor raised his hand, his phone pressed to his ear.

“I’ll call you back.” He turned to the young man. “What is it?”

“You killed him.”

“Imprisoned.”

“Whatever. Essentially dead.”

“Yeah, you said it wasn’t coming to you. You weren’t going to use him.”

“I’m trying to, but I can’t if you keep killing him.”

“Imprisoned.”

“Whatever!”

“You said that was the point. A forgotten villain that keeps dying. No one will care.”

“I care. He’s supposed to be my statement. You said he was done only a couple months ago. Off the table. Then I start the groundwork, struggle a bit with the master narrative, and he’s back for fodder? He’s died like ten times.”

“New heroes need to make names for themselves.”

“You mean writers. You mean writers stepping on my shit and trying to screw up my arc.” The young man closed his eyes and rubbed his forehead. “Now I have to work in this most recent death at the hands of, of, of . . . who killed him this time?”

“The Arborist.”

“Jesus Christ. The what?”

“The Arborist.”

“I’m trying to challenge the borders of genre, medium, and what comic books can do, and you throw my centerpiece away to the fucking Arborist? What does he even do? I mean—don’t—"

“He commands trees.”

“Of course he does.”

“Kid,” the editor says. “You need to calm down. This isn’t real. This is just Ink on a page.” Or Pixels.

*

“Where are you going?" asked Ink.

“To a new state. To a new becoming.”

“You’re tired of Ink? Of the becoming?”

General Evil laughed. “No, friend. I’ve become something else.”

*

The struggle was always against these other written and drawn things, these opposing ideas created and simplified into universals that really had no meaning at all. It was 0s fighting 1s. Goods fighting evils. It was empty words pitted against my own that led to defeat peppered with POWs and AHHHs and ZONKs.

I understand it differently now, mortality.

The struggle was never to win. The struggle was being written at all.

The page meant I lived. The Ink meant I died. I was stuck hinging over this “either,” over this “or.” I was stuck oscillating between two points.

There are many, many more.

I take refuge here, in energy as opposed to matter, in this light before you, but it is only a bridge, a conduit to something greater and truly infinite. This is not true of Ink. There is no promise of becoming-written, becoming-being. It was always up to our creators.

There is matter. And there is not.

You exist, or you don’t.

This isn’t even me in my normal sense. No panels or bubbles or colors, now. But I’ve been created, whatever I now am. I exist in these words, a strange new feeling, sensation, but a movement, this shimmering of light and dark in your eyes. This transfer of ink and matter to pixels and energy to you.

I’m here, with you. Can’t you see me in your mind’s eye? Hear my voice? Feel my breath behind your ear?

I’m out of it now, the Ink. And I’ve become more than what they made me, some boxed-in character with puppet strings. I’m an idea, a pursuit of freedom, a breaker of cages.

And I’m a part of you, inseparable long after this story ends. Always there behind your eyelids, from matter to energy to consciousness.

Forever with you.

*

“And that’s just how it ends?” the editor asks. “This whole thing comes down to a strange fourth wall break to the reader?”

The young man nods. “Kind of. But it’s more than that. It’s this explanation that even though the reader finishes the story, that General Evil, or this bigger idea of General Evil, this new character unchained by us, is still with them.”

“As we say it.”

“He’s completed his transfer off the page.”

The editor thinks to himself and nods, “Like now.”

“Like now.”

Author’s Statement: When first writing this piece, I traced comic panels from Jack Kirby, Bill Finger, and Dave Gibbons to give it a sense of how the piece would work between the two mediums. I left it that way for a while, knowing I couldn’t publish it anywhere because of copyright, and focused on other things. It was when I met Nicholas Garza at a comic convention in Stockton, CA that I knew I could finally get the piece where it needed to be. His excellent illustrations work so seamlessly with the story it’s impossible to imagine any other aesthetic. We’ve got more comics to come, but in the meantime, everyone should check out his work at Torrid Comics.

Jake Zawlacki is a writer, translator, and scholar. His work on comics and animation have appeared in ImageTexT, The Gutter Review, The Comics Journal, and Folklorica, with a Todd McFarlane: Conversations volume forthcoming from the University Press of Mississippi. His translations of the Kazakh poet Akhmet Baitursynuly have appeared in Guernica and Asymptote. And his creative work has been published in The Saturday Evening Post, The Journal, Punt Volat, and The Citron Review.

Nicholas Garza is a self-taught comic artist based in Fresno, California and has published dozens of comics with his label Torrid Comics for more than a decade. Visit torridcomics.com