Giving Pictures

/Jeff Hoffmann

When my wife and I quit our jobs and fled the country, we brought our rubber chicken. It started as part of a Halloween costume, but it had become a mascot of sorts, surfacing at parties and bars and weddings. It travelled with our friends to different cities and returned with pictures of its exploits. You can drink beer out of the chicken, and it becomes a limbo bar if you stretch it, and when we offered a $100 bounty to anyone who could fit it in their mouth, lines formed. It was like a garden gnome, but lighter, more useful, and easier to pack. By the time we left the country, the question wasn’t why would you bring a rubber chicken? but rather, how could you not?

*

We fled in September of 2000. We had recently turned thirty, and too much work in our twenties – sixty to eighty hours a week for a decade – made our escape both possible and necessary. Sara and I were fleeing my work, for sure. And children awaited our return. We both wanted a family, looked forward to it, but we weren’t ready yet, and I guess that we ran from that as well. All of our friends were having children. Our calendar had become littered with christenings and first birthday parties and babysitting infants for their exhausted parents. This trip would be our epic. This was before we knew that autism would come home with our daughter, making a weekend in the Wisconsin Dells more daunting than the Odyssey, but the decision had become binary: procreate or evacuate.

*

We learned to say chicken in many languages. In Maori, they call it heihei, in Australian, chook, in Khmer, sach mean, in Thai, ki, in Chinese, ji, in Arabic, dijaj. And we learned that no matter the culture, a rubber chicken is the ultimate icebreaker. When you pull a rubber chicken from your pack, nobody can contain their smile. Even the shyest agree to a picture. Friendships become inevitable.

We took a picture of a gondolier in Venice and Masaii tribesmen on the plains of Tanzania and a group of Roman soldiers in front of the Coliseum and a monk at Angkor Wat and a woman in a Bangkok alley hammering copper alms bowls and a beer wench at Oktoberfest and a man in Melbourne carrying a large slab of meat over his shoulder – all holding our rubber chicken. We took pictures of locals and travelers and hosts and guests and new friends and many, many, many strangers, holding our rubber chicken. We took, and we took, and we took, and we took.

*

In India, they call the chicken a murga. We were gone eight months before we found ourselves in Agra. We quickly learned that photography, like everything else in India, would prove different. Indians are very proud of the Taj Mahal – it’s their Statue of Liberty and Golden Gate Bridge and Grand Canyon rolled into one, so when we snapped a photo of me holding the chicken in front of the marble behemoth, a security guard swiftly took it into custody. We could pick it up at the ticket office when we left, he said.

Several hours later, Sara and I sat on a low wall near the Taj, enjoying the garden that unspooled for a half mile to the south. A reflecting pool ran through the center of the garden, and shrubs flirted with the water, curving away from it and then snaking toward it, just to dart away again. A mother began to arrange her family right in front of us. We gathered our things and made to move, well-used to Indian elbows by then. No, no, the woman assured us. She wanted the Americans in the picture. We stood awkwardly next to the family, smiling, the tourists turned prop for the locals.

When I knocked on the door of the ramshackle ticket booth, I didn’t really expect to see the chicken again. And it occurred to me that if I couldn’t even properly look after a rubber chicken – clearly I wasn’t ready for children. The door opened, and a man in a white button-down shirt with yellowing armpits scowled at me. Two more men sat at the windows slowly doling out tickets to the throng of families elbowing their way to the front of the line. When I asked for my rubber chicken, the man frowned, said something in Hindi, and shook his head. When I asked for the murga, his face lit with a smile. Murga? he asked. Yes, I said, the murga. The other two men heard us and turned with smiles of their own. The man at the door rummaged through a pile of lost items on a shelf and produced the chicken. Clearly the guard had told him what we had been up to, because he clutched it by the neck and said, You take our picture first.

*

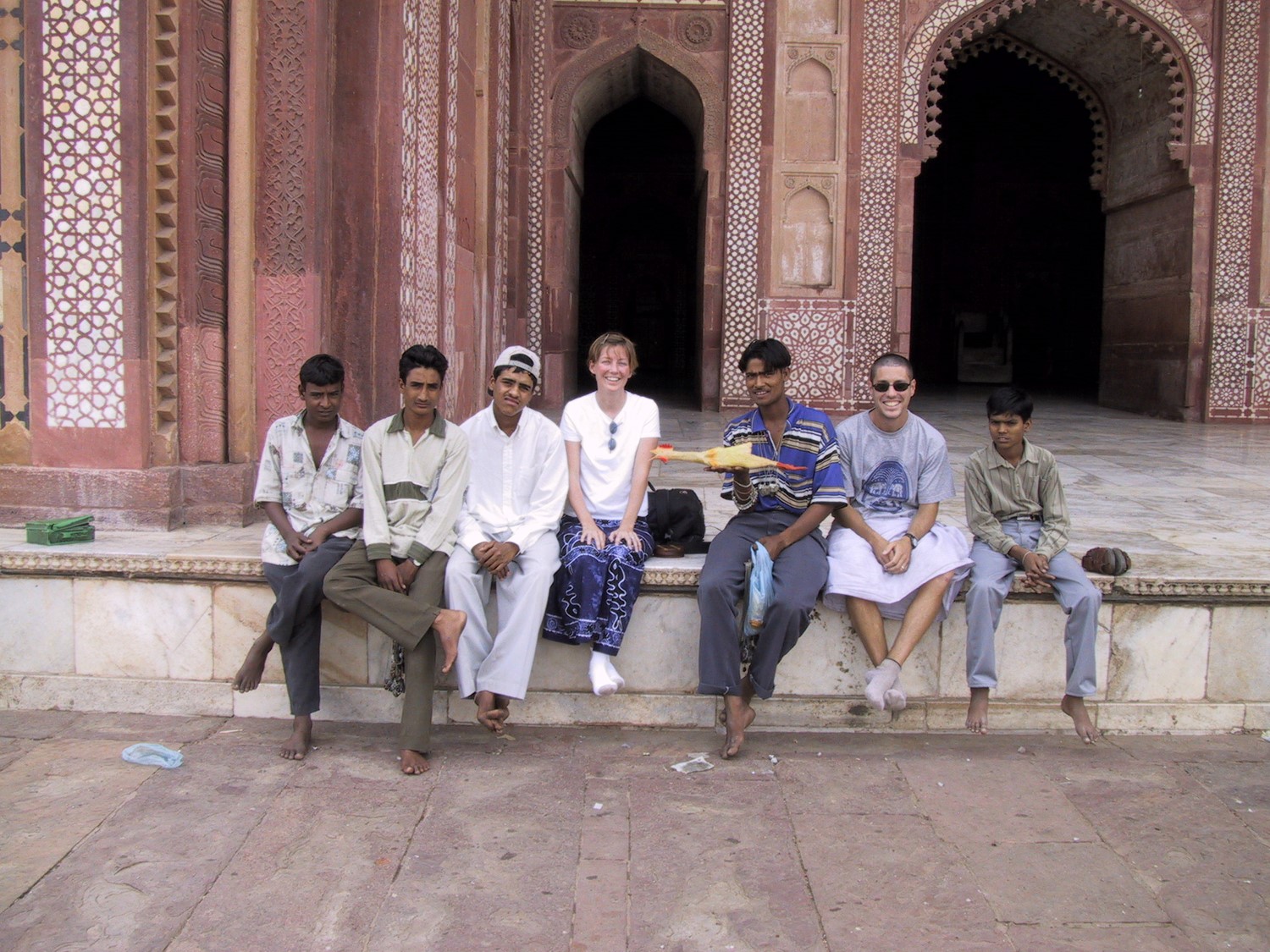

The chicken caused trouble again at Fatehpur Sikri, a red sandstone fortress perched on a rocky ridge, forty miles outside of Agra. Built in the sixteenth century as the capital of the Mughal empire, the mosque and palaces are littered with domes and minarets and arcades, surrounding an enormous square paved with stones of red and pink and tan. We were the only foreigners in sight.

As soon as Sara pulled out her camera, boys began asking her to take their picture. A family did the same. We had nothing to give in return, so I pulled out the murga. Smiles burst. A boy plucked it from my hands and knew just what to do – he stood in the square clutching the chicken by the throat. We took a picture. A crowd materialized, a half-dozen boys, then a dozen, then two dozen, a few young men, a little girl. Everyone grabbed for the chicken as they squeezed into the frame, grinning. We took the photo, and that satisfied everyone for a moment, but then the boys began to shove and scuffle. An unsmiling guard appeared and took the chicken from the mob, gave it back to us, and told us in very clear terms to put it away or leave.

I tucked the chicken back into my pack, and the crowd reluctantly dispersed. A half-dozen teenagers lingered, and we sat with them for an hour on the steps of the Queen’s Palace. We quickly dispatched with the inevitable discussions about Michael Jordan and Al Capone (bang, bang) after we told them that we hailed from Chicago. They described their village and their lives and their dreams. One would become a doctor, another a school teacher, the others just shrugged and smiled like my teenage son does now. They asked us (as most Indians did) if we had children, and when we said no, they said (as most Indians did) that they were terribly sorry. I didn’t tell them that there was no reason to be sorry, that we weren’t ready for children yet, and Sara wasn’t obliged to point out that it was really me who wasn’t ready for children yet. We tried to tell them about our own lives and about Chicago in a way that seemed relevant in the desert of Uttar Pradesh. As the sun fell, we readied to leave. The oldest boy, wearing a green baseball cap and mirrored sunglasses, nodded toward my bag and asked if we would take his picture with the chicken. I glanced at the guard who had not strayed far. I’m not sure that’s a good idea, I said. Take a picture of me, then, he said. So we took that, too.

*

After Fatehpur Sikri, as we made our way westward across Rajasthan, the chicken spent more time in my bag – an icebreaker was laughably un-necessary in India. People approached us on the street, some offering to take us to the carpet factory their cousin owned, many to practice their English, others just to meet us, to talk a bit. Everyone asked us if we had children, and all of them told us how sorry they were when we said no. At a crowded festival for Parvati, the Hindu goddess of fertility, we were followed by a pack of children as we entered the fairgrounds, and then surrounded by a mob of families who just wanted to be near us, to touch us. We literally had to flee for our own safety. And everywhere we went, families and children and grown men alike all asked us to take their pictures, and we took, and we took, and we took.

That woman in Jaipur finally made us feel greedy. We had just left Hawa Mahal, the Palace of the Breeze, five stories of honeycombed windows carved into the pink and red sandstone. Almost a thousand tiny latticed windows, to welcome the wind and to allow the royal woman to peer modestly at the action outside without being seen. We were walking through the nearby markets, and Sara was taking a picture of a monkey climbing up a gutter with its baby clinging to its belly, when the woman spotted the camera.

She lacked the reticence that I imagined for those women who had hidden behind the latticework so many centuries ago. She darted with her daughter through the torrent of cows and motorcycles and large white cars that served as a street. In broken yet insistent English she told us that we would take their picture more than she asked. She adjusted her daughter’s yellow sari and murmured to her in Hindi – presumably to stand up straight and to smile. The woman wore a scarf, and her daughter’s head was bare, but the bhindis in the center of both of their foreheads gleamed an identical scarlet. She thanked us twice, before disappearing into the crowd, leaving us with the picture and taking nothing but her memory of giving it. We had finally grown bloated with the taking.

*

After Jaipur, we flew to Udaipur, The City of Lakes. Back then, you could stay in former palaces turned hotels for about a hundred dollars per night. Sara was willing to live adventurously in Australia and New Zealand and Europe, but India is unpredictable on the best day, so in India she demanded the life of a Sultana. When a palace was available, in a palace we stayed. Udaipur’s Lake Palace stunned us. Built 250 years ago entirely of brilliant white marble, its walls rise straight from the center of Lake Pichola like a dream. Sara and the chicken held court in the palace while I took a boat to the city, determined to find a camera better suited to our circumstances.

A half million people call Udaipur home – more of a town than a city by Indian standards – so I walked from the dock into the shopping district. In India back then, every store was highly specialized – maybe they still are. The pen shop was down the street from the notebook seller. A hammer could not be had in the shop that sold nails. Before long, I found a camera shop and walked past the small metal table surrounded by men drinking tea (men seem to drink tea in front of most shops), and I went inside. The shopkeeper was patient as I tried to explain what I was looking for, but I only managed to bewilder him. This was before a camera would live in every cell phone, but well after Polaroid’s heyday. The men drinking tea drifted inside to see if they could help. The word Polaroid earned me more blank stares. I pretended to shake an invisible photo, holding it by the corner between my thumb and forefinger. Their brows wrinkled. Instant, I said. Instant. Finally, recognition dawned on the face of one of the tea-drinkers. Ahhh, Polaroid, he said, and then something else in Hindi. No, the shopkeeper said, shaking his head. No Polaroid. The tea-drinker assured me that he would take me to Polaroid, as if it were a place. Still not sure I was understood, I climbed into his car.

At the third camera shop, after walking past the men drinking tea around another small metal table, and after much discussion and several of those uniquely ambiguous Indian shrugs, a dusty box with a Polaroid camera was miraculously produced from the back room. It was the boxy gray model from my childhood, the one so big that it folds upon itself so that it might fit in carry-on luggage. We quickly agreed to a price of many rupees. I wasn’t in a position to negotiate, and the fee had to include a hefty commission for my driver. I asked for film. Film? No. No film. My driver grinned. I will take you to film.

The fourth store had no Polaroid film. We revisited the first and then the second store, saying hello again to the men drinking tea around the small metal tables. The owner of the second shop unearthed three foil-wrapped packages. The film cost a bit more than the camera itself. Batteries? No. The shopkeeper shook his head mournfully. No batteries. The tea-drinkers murmured. My driver smiled.

*

We flew from Udaipur to Jodhpur and then drove from Jodhpur to Jaisalmer. The flight was uneventful, the drive terrifying. Our driver owned a white Ambassador, of course, the ubiquitous hulking steel Model T of India. In town, the swarms of motorcycles and cows and buses and Ambassadors, made for a cacophony of horns, but didn’t allow for speed. On the open road between Jodhpur and Jaisalmer, though, our driver averaged 100 kilometers per hour right down the center of the two-lane road. The margins along both sides were cratered with potholes allowing for only one usable lane. When our driver saw another Ambassador coming toward us from the west, he would accelerate. Both drivers barreled right toward each other, neither willing to surrender the smooth pavement of the center. They honked their horns insistently, swerving only at the last second, and only enough to keep their side mirrors from colliding, a terrible and senseless game of – well – chicken.

We were facing five hours of this, so, to distract herself, Sara started in about the kids. We quickly agreed that we’d try as soon as we returned home, if not sooner. We haggled about how many and agreed upon a number somewhere between two and three. We brainstormed their names and considered where we would live. This all assumed, of course, that we would survive the day. And we didn’t yet know that we would adopt our children from two countries bordering India. We didn’t yet know that our daughter would struggle and that we would trade the chicken for sensory toys and therapy – physical therapy and occupational therapy and speech therapy and ABA therapy and listening therapy and Feldenkrais therapy and five other therapies that I’ve long since forgotten. We didn’t yet know that autism would be the easy part.

*

Jaisalmer is the last stop on that long road through Rajasthan. Sand dunes stretch past it to the west and to the border with Pakistan. It was also our last stop in India. After Jaisalmer, we would make our way back to Delhi and then fly to Kathmandu, the city we would return to in a few years to adopt our son. We dutifully toured the fort (built of sandstone of course) and then wandered through the ancient city. It is nine hundred years old, but most of it seems older. The streets became alleys and they snaked, and they twisted, and became rubble-filled paths shared with donkeys and cows and littered with hand-painted signs promising INTERNET and EMAIL, and soon we were hopelessly and deliciously lost. A girl in a green sari, just a little bit younger than my daughter is now, saw Sara’s camera and asked us in her best English to please take her picture. She stood thin and straight against a whitewashed stone wall, a grim look on her face. I focused the Nikon while Sara manned the new hardware. When the strange gray box began to click and whir, the girl cocked her head. When it spat a blank white square of vinyl, her eyebrows bunched. When Sara handed her the square, the girl looked from it to Sara and back again, thoroughly confused.

When a green smudge began to appear on the white, the girl’s eyes fixed on it. When that smear slowly melted into her image, a smile finally bloomed. She looked at Sara one more time, eyebrows raised in a question. Sara nodded and smiled, and the girl raced down the alley, shouting. Doors and shutters opened. People appeared. She showed them the photo of herself, chattering excitedly. She pointed at us, and her neighbors darted indoors, returning moments later, dressed in different clothes, presumably their best. For the better part of an hour, we gave pictures even as we took them.

One tall, middle-aged woman stayed at our elbow, insistent. She pulled us to her doorway at the end of the alley and invited us into her home. We watched as she applied kohl to the eyes of her infant grandson. She handed the boy to her mother and disappeared into the next room. I could tell that Sara was itching to hold that baby, but something held her back from asking. The woman returned wearing a muted white sari spackled with sunbursts. Large gold earrings dangled to her shoulders, and bangles covered her wrists. Her mother handed the boy back, left the room, and returned wearing a matching sari and a magenta headscarf. They arranged themselves on the stone steps leading into their house, the older woman holding the baby. They almost smiled.

*

Almost twenty years later, the chicken now roosts in our attic, and the chicken pictures are tucked away in the cloud somewhere, but the photo we took of those three generations still hangs on the wall of my living room, near pictures of my own children with their grandparents. The Indian women dressed in saris might make some people wonder, but the Asian baby fits right in. I like to the think that the photo we gave still leans on a shelf in that home in Jaisalmer. Certainly, the decades and technology have transformed that dusty city where the road ends, but I sometimes wonder if the boy’s mother still occasionally points to that faded image when her son returns home from Mumbai, reminding him what he looked like as a baby, but more importantly, what his great-grandmother looked like before she died.

(Please click on pictures to view the gallery)

Jeff Hoffmann's writing has recently appeared or is forthcoming in The Sun, New Madrid, Harpur Palate, Booth, Barely South, and Lunch Ticket among others. He won The Madison Review's 2018 Chris O'Malley Prize for Fiction and is completing a novel based upon that story. He lives near Chicago and is pursuing his MFA at Columbia College Chicago. You can learn more about Jeff and his writing at www.jeffhoffmannwrites.com.